The Garden That Keeps On Growing

By: Theresa Krakauskas

As I was watching a marathon of movies adapted from V.C. Andrews books on Lifetime last weekend, I wondered if, as an actor, Jason Priestly ever choked on the dreck coming out of his mouth. Finding out during the commercial break trivia that he’d directed Fallen Hearts (one of the Heaven series), it brought me to another question. Why was I watching this dreck? Which led to an even bigger question, why did I, along with millions of others, love it so much in the first place?

Born Cleo Virginia Andrews in Portsmouth, Virginia, Andrews suffered a fall that led to her being disabled from the age of 15. She spent most of her life in a wheelchair or using crutches, but never let it slow her down. She excelled in school, and after a four-year correspondence course in art, had a successful career as a commercial artist, fashion illustrator, and portrait painter. Not satisfied creatively with her work, she took to writing in secret. At around age 50, she completed her first novel, Gods of Green Mountain, a science fiction fantasy, and wrote nine novels and twenty short stories between 1972 and 1979. According to her 1979 pitch letter for Flowers in the Attic, sent to literary agent Anita Diamant, she said she’d sold three gothic romances under a pseudonym, and had also written confession stories for pulp confession magazines. Her story, I Slept with My Uncle on My Wedding Night, certainly sounds like it paved the way for her subsequent best sellers.

Eventually Flowers in the Attic ended up in the hands of Ann Patty, a young editor at Simon and Schuster’s Pocket Books division. Patty has said, when she read it, she thought, “It’s like a crazy fairy tale. [Andrews] had a particular style. You wouldn’t call it a good style, but it was a style. It was so unique. I just thought I’d never read anything like this. Never.” After meeting Andrews, and realizing she was disabled, Patty said, “And then it all became clear: [Andrews] was that teenager. If you think about her emotional life and her experiences and independence – which there was none – her life kind of stopped when she was about 14 or 15.” Patty was right on the money, as in a rare interview published in the 1985 book, Faces of Fear: Encounters With the Creators of Modern Horror, Andrews told Douglas E. Winter, “When I wrote Flowers in the Attic, all of Cathy’s feelings about being in prison were my feelings. So that, when I read them now, I cry.”

In case you’re the rare person who doesn’t know the plot, Flowers in the Attic is the story of the Dollanganger children, told from the viewpoint of the oldest daughter, Cathy. She, along with older brother Chris, and younger sibling twins Carrie and Corey, have their idyllic lives ripped out from under them when their father dies in an accident. Deeply in debt, their mother Corinne takes the children to her ancestral family home, Foxworth Hall. Unbeknownst to the children, Corinne’s husband (their father) was also her father’s half-brother. When their love was discovered, Corinne’s father Malcolm disowned her, and tossed them both out. Corinne tells the children that her father is on his deathbed, and if she gets back in his good graces, she’ll inherit a fortune, but in the meantime, they must hide in the attic. She’s assisted by her mother Olivia, a religious zealot who abuses the children, and calls them an abomination and the spawn of Satan, “a stain on the Foxworth name and the Lord Himself.” Promised it will only be a short time, the children end up staying in the attic for three years. While Corinne does get back on the right side of her father, his will stipulates that she inherits nothing if it’s discovered there were any children from her marriage. Corinne begins to visit the children less and less, and their grandmother becomes more abusive. Eventually, Corinne marries her father’s attorney and takes off for an extended honeymoon in Europe. She fails to tell her new husband about the children as well, and begins to slip arsenic into the powdered donuts they’re given as a treat. Young Corey dies, but Corinne tells the other children it was pneumonia that killed him. During their imprisonment, Chris and Cathy do their best to take care of the twins, and create their own amusement, including a paper garden, whose flowers hang from the attic ceiling. The older children become attracted to one another, and in a fit of rage, Chris rapes Cathy. He’s overcome with remorse afterward, but Cathy tells him that she wanted it too. After their mother remarries, Chris and Cathy realize their liberation isn’t happening, and decide to hatch a plan of escape, Chris making a copy of a skeleton key stolen from their grandmother. They begin to steal money from those in the house, discover their grandfather has died, and find out about the plot to poison them that caused Corey’s death. Finally escaping Foxworth Hall, they decide not to contact the police, wanting to protect the still young Carrie, but Cathy swears she’ll get revenge one day.

As shocking and twisted as the plot is, what’s even more bizarre is how badly written the books are. In The Southern Gothic Novels of V.C. Andrews, Ashleigh Condon says, “The amazing thing about V C Andrews’ writing was that, in many cases, it was actually so bad it was good. Her characters spoke in a highly dramatic and unrealistic way, and yet it’s what keeps you turning the pages. The twists and turns were outlandish too, almost too bizarre, which meant that you could never ever guess where it was going next. Her characters were ultimately flawed by their lack of self-control when it came to their needs.” Condon is spot on in her description, the dialog consistently weirding me out with its lack of contractions in a modern-day world. Yet I couldn’t turn away.

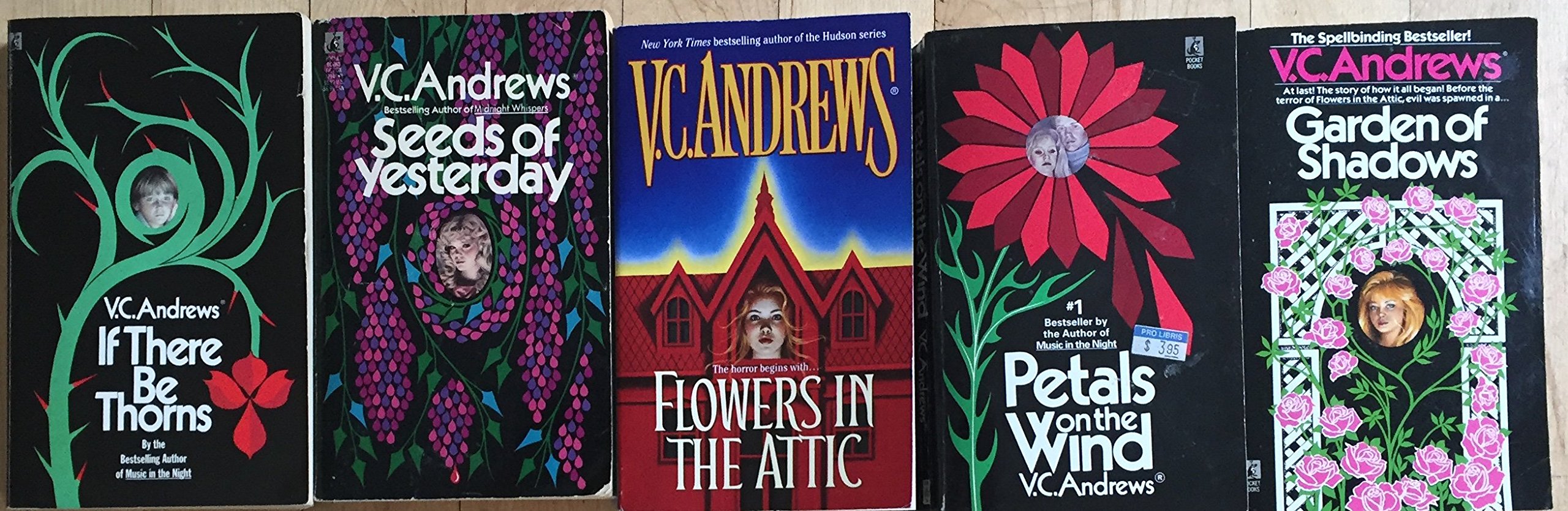

What happened next was no less than a phenomenon. Published in 1979, Flowers In The Attic was an immediate best seller. Andrews claimed to have written it in two weeks, and within two weeks it went to the top of the best seller lists. She followed it with four more books about the Dollangangers; Petals on the Wind, If There Be Thorns, Seeds of Yesterday, and Garden of Shadows. In between, she also wrote a stand-alone book, My Sweet Audrina, a novel about a young girl haunted by the rape and death of a sister who died nine years before she was born. Andrews followed with another series, this time about the Casteel family, whose father sells daughter Heaven to a cruel and unusual family. The only series based on the grain of a true story, it began in 1985 with Heaven, and continued on with another four books. In 1986, after the second book in the series was released, the American Bookseller’s Association named Andrews the Number One Best Selling Author of popular horror and occult paperbacks, Andrews beating out Stephen King. According to Simon and Schuster, Andrews is one of the best-selling authors of all time, and there are more than eighty V.C. Andrews novels, which have sold over 107 million copies worldwide, and have been translated into twenty-five foreign languages.

But here’s where the real life strange comes in. Andrews passed away from breast cancer in 1986. According to sister-in-law Joan, Andrews knew she had a lump in her breast, but refused to deal with it until she was done writing Heaven and its sequel Dark Angel, and by then the cancer had begun to spread. Working through her health issues was nothing new to Andrews. Because she couldn’t sit in a desk chair for long periods, she spent ten to twelve hours a day standing at her typewriter, and according to her editor, the soles of her shoes were worn through, and bones protruded from the bottoms of her feet. After she died, Garden of Shadows, the prequel to Flowers in the Attic, was not yet finished. Simon and Schuster prepared a memo for their staff saying Andrews had been writing until the time of her death, and had a number of unpublished novels remaining. While her death was listed in the papers, it wasn’t exactly front page news, and in the meantime novelist Andrew Neiderman was brought in to continue Andrews’ work, having the same agent and editor. He worked from material Andrews had left behind, which he later admitted “wasn’t much,” and then continued ghostwriting under her name, churning out several novels a year.

Neiderman has reason to be proud of his work under his own name, his most recognizable book being The Devil’s Advocate, made into a movie starring Keanu Reeves and Al Pacino. This film is a personal favorite of mine, and I think the best depiction of the devil since the Bible made him famous. Of course he’s a head of a law firm! When asked by the host on the Today Show in New Orleans how he tapped into writing from a feminine viewpoint, Neiderman was somewhat annoyed, having had no time to prepare, and said, “Well, in the morning, I put on my wife’s nightgown and high-heeled shoes, and start to type.” The host was taken aback, and after counting to three, Neiderman said he was kidding. His real process was to write on two computers, channeling Andrews on one of them.

While Simon and Schuster didn’t hide the fact of Andrews’ death, they continued to be hazy on just how much material was left behind, until 1991, when Andrews’ U.K. publisher was outbid for Dawn, and outed Neiderman. Pocket Books acknowledged Neiderman’s ghostwriting existence, and a letter from the Andrews family stated, “Beginning with the final books in the Casteel series, we have been working closely with a carefully selected writer to organize and complete Virginia’s stories, and to expand upon them by creating additional novels inspired by her wonderful storytelling genius.” They promised more novels in the coming years, and Neiderman has continued to keep that promise.

A theatrical film of Flowers in the Attic was made in 1987, starring Louise Fletcher as Olivia, Victoria Tennant as Corrine, and Kristy Swanson (the original cinematic Buffy, the Vampire Slayer) as Cathy. It didn’t do well, as the script veered from the original story, leaving out the relationship between Chris and Cathy, and changing the ending to the point where it was unrecognizable to fans of the book, and left no room for the sequel where revenge is taken. In 2014, the Lifetime network took another stab at it, this time doing right by fans, the script following the book practically word for word. It was such a success, they continued the saga, as well as producing a series of films on the story of the Casteel family as well.

Which brings me back to why. Why on earth are these creepy stories beloved, not just by the teens and young adults they’re geared toward, but even by established and respected authors? Anne Rice has said, “[Andrews] touched a nerve. Many identified with her suffering children in the attic. And the simple style of her book appealed to many young people.” According to Sarah Weinman, news editor at Publishers Marketplace, “It’s the same reason Jane Eyre resonated with people. It’s why gothic novels have always found an audience; it’s why romantic suspense has always done well. It’s this feeling that readers can fall into; they get absorbed by all the characters. They get caught up in the calamities. There was a great melodrama to what V.C. Andrews was writing.” Gillian Flynn, best-selling author of Sharp Objects stated, “I will probably be clutching Flowers in the Attic in my gnarled hands on my deathbed,” and Neiderman himself has said, “She was driven by the question that drives all of us. Why do people who are supposed to love each other harm each other in such ways?” Lizzy Goodman of The Guardian described Andrews’ novels as “a hybrid of Peyton Place, The Thorn Birds, and American Horror Story,” saying, “pop culture is not proportional to its emotional resonance.” I guess that explains pet rocks and smiley faces, as well as plenty of other silly, but beloved fads over the years.

Perhaps it’s part of the explanation as to why Andrews’ stories hit us in such a way. Or maybe we can forego absurd dialog for the substance of the plot. Or possibly, the Foxworths, along with the other heads of Andrews’ fictional families, represent our fear of abandonment, and the protagonists our hope for triumph over our fears. Or I could just go basic, and say it’s pure entertainment and tickles our fancy for the macabre.

Before her death, Andrews said, “All my life, I thought I was meant to be something special. I never knew what it was. Now I have the satisfaction of having my name recognized, and it will live after me.” And maybe that’s part of it too. Our desire to keep going through adversity, and leave something behind to be remembered by.