Evolution of TV: Where Do We Grow From Here?

By: Theresa Krakauskas

Gather around while I put on my shawl and tell you about when television was first invented. Okay, I’m not that old, but there was a time when people didn’t have screens in front of them 24/7. While I don’t remember life before any screen, I did grow up in a world with only three networks, plus a mysterious zone called UHF where PBS lived. As if that wasn’t bad enough, TV stations signed off somewhere around 1 am, to the tune of The Star Spangled Banner. Even today, when I hear that piece of music, nothing can get me lunging for the nearest remote faster – which can be pretty embarrassing in a stadium. Things finally changed for this night owl after I moved to the big city, and discovered a network called 9 All Night, and I watched whatever crappy movie they were showing, usually such gems as The Brain That Wouldn’t Die or The Incredible Two-Headed Transplant (not Rosey Grier’s finest moment). I was a desperate woman, as TV had been my background noise practically since birth. Raised by my father, I was a latchkey kid before there was a word for it, and in that free zone between getting home from school and my father getting home from work, TV was my babysitter. When I got my first color TV – not an affordable option in our household – you’d have thought I never saw color before. More networks began to be added, and then came cable. Again, unaffordable for me, a single person living in Manhattan, but I would go to a friend’s apartment in Greenwich Village, where we watched the beginnings of MTV, which started off with a whole three videos shown over and over. I also discovered, that if I set the channel changer in between certain stations, I could tune in to a fuzzy HBO. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

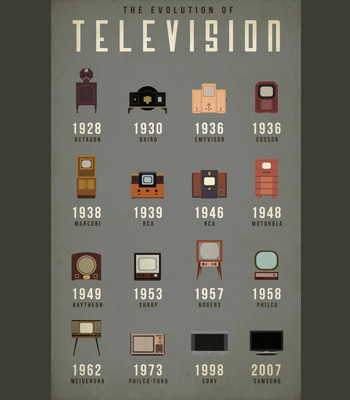

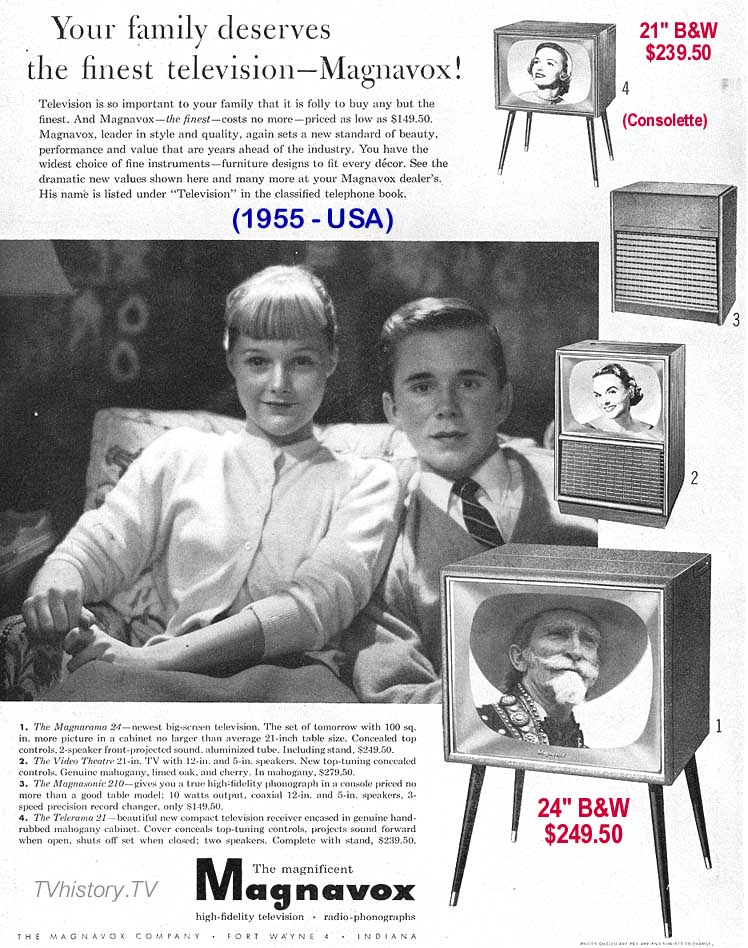

The earliest version of a television was the Octagon, made in 1928 by General Electric. The cabinet was bigger than the three-inch screen, and it used rotating disc technology. It wasn’t widely produced, and few are left, but it was believed to have played television’s first drama, The Queen’s Messenger, where a British diplomat carrying secret papers for the queen has a romantic encounter with a mysterious Russian woman. In 1936, the Cossor television came along, costing somewhere in the neighborhood of $350, or $6500 today. Again, the cabinet was much bigger than the 13” screen, and it’s brochure advertised, “Radio – its thrills, its interests, increased one hundred fold by Television… Radio is blind no longer. The most exciting running commentary is made immeasurably more thrilling when you can SEE too!” Televisions eventually gained (literal) legs, bigger screens, and by the mid-1950s, were mass produced, costing around $250, still a hefty sum, being just about $2400 today. Still, the number of television sets in use in the United States rose from 6,000 in 1946 to more than 12 million by 1951. Eventually, television sets became more affordable, buttons replaced knobs, screens got bigger then flatter, and TVs ultimately became “smart,” and able to access other media content.

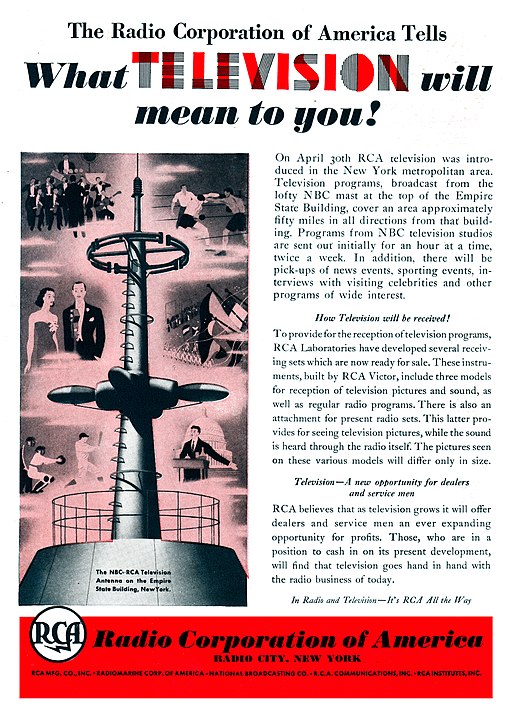

Broadcasting itself began as early as 1928, when the Federal Radio Commission authorized inventor Charles Jenkins to broadcast from W3XK, an experimental station in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, DC. In 1939, NBC, then a subsidiary of RCA, became the first network to transmit regular broadcasts, starting at the opening ceremonies of the New York World’s Fair. World War II nearly halted all broadcasting, when companies that made sets concentrated on making military equipment. Networks reduced their programming to four hours a day, or went off the air altogether. Television came back strong in the 1950s, considered the golden age of television, when “mass-production advances made during World War II substantially lowered the cost of purchasing a set, making television accessible to the masses. In 1945, there were fewer than 10,000 television sets in the United States. By 1950, this figure had soared to around 6 million, and by 1960 more than 60 million television sets had been sold.” (World Book Encyclopedia – 2003)

Until the fall of 1948, there wasn’t much in the way of regular programming. To encourage sales, sports broadcasts were scheduled on weekends to entice heads of households to purchase sets. Much of TV viewing before then took place in taverns and local appliance stores, where TVs were demonstrated. At first, there was only news coverage, footage being provided by newsreels, and formats of programs based on radio shows. In the 1950s, programmers borrowed from theater, giving viewers Playhouse 90 and the US Steel Hour. Early programs had single sponsors, giving the advertiser an excessive amount of control, but when magazine formatted shows and variety shows changed the standard radio length of 15 minutes to 30 minutes, networks were able to charge more for advertising, and prohibited single sponsors. The Tonight Show premiered in 1954, with short segments, and ran several hours. Shown daily, it increased advertising costs, and music-variety shows, known as television spectaculars (what we now call specials) had multiple advertisers. Single sponsors still made out though. By the mid-1950s radio quiz shows were brought to TV, and a single corporate sponsor’s name ran throughout the show. Not unlike today’s programming, where if something catches on, every network churns it out, by the 1957-1958 season, 22 quiz shows were being broadcast. Popularity dropped when it was discovered the shows were rigged, finding that answers were given to most likeable candidate to increase viewers. Quiz Show, a 1994 film starring John Turturro, gives a fantastic account of the scandal. The disgrace was so embedded in the minds of the public, the genre wasn’t revived until 1999 with Who Wants to be a Millionaire.

Movies were expensive and time-consuming, and until the mid-1950s, Hollywood considered television a threat. Many early TV shows were based on radio programs, some of which were even simulcast for years on both media. However, in many cases, scenes that could be implied on the radio couldn’t be reproduced cheaply for cameras. Because videotape wasn’t used much until the 1960s, live transmissions of musical performances, sporting events, sermons, and educational lectures were broadcast. By the 1948-1950 season, the highest rated programs were variety shows, like The Ed Sullivan Show, with an emcee, an audience, and a variety of guests. Comedy variety shows also did well, such as Your Show of Shows (1950-1954), which brought us Carl Reiner, and Caesar’s Hour (1954-1957), whose writing staff included Mel Brooks and Neil Simon. Stage plays and classic literature were also adapted for television. Other genres were borrowed from the radio, and westerns, crime dramas, and game shows were the top shows of the 1950-1951 season. Popular on radio, sitcoms were slow to gain favor on television. One of the most popular sitcoms in history, The Honeymooners (1955-1956) began as a sketch comedy on a variety show, not too different from how we ended up extracting The Simpsons from The Tracey Ullman Show. I Love Lucy was born in 1951, and established the standard, creating a television revolution. During the 1953-1954 season, the percentage of U.S. households with television sets climbed to over 50%, television became a mass medium, and programming started to improve.

While Vietnam was our first real televised war, correspondents reported from the field during WWII and the Korean War. Politics and in-depth news about current events also became a staple. When Senator Joseph McCarthy made anticommunism his issue, he became a TV star of sorts, which led to the blacklisting of many in the entertainment industry, regardless of evidence. In turn, programming became sparse. However, television also became McCarthy’s undoing, when reporters Edward R. Murrow and his partner, Fred W. Friendly, exposed McCarthy for the liar, hypocrite and bully he was. Hollywood, which had originally distanced itself from television, began to branch into the business. Many live programs were replaced by filmed productions, and by the end of the 1960s, the only live broadcasts were sports, news, and a few soap operas. Filmed shows also generated more revenue, as they could be repeated in syndication. With televisions now being in more households, by 1959 increasing to 85.9%, the demographic also changed, and programs began to reflect that. The longest-running fictional series on primetime (at least for the remainder of the century), Gunsmoke, was popular because it adapted to the country’s changing values and cultural styles. Using its western setting to depict social issues, it included rape, civil disobedience, and civil rights in its plotlines. However, most of the sitcoms, Leave It To Beaver (1957-1963) for example, did not reflect reality, and portrayed families as living in a perfect world where nothing really bad happened, and all minor problems were sewn up in thirty minutes. The Golden Age of Television ended, when along with the quiz show scandal, The Untouchables (1959-63) premiered. Influenced by film noir, it was an historical drama about organized crime during the Prohibition era in Chicago. By the 1960s, television dominated mass media. The 60s gave television the most diversity in genres until cable came into play.

In the 1970s, although there were still limitations, the perfect sitcom family gave way to a more realistic view of the world, with shows like All In the Family (1971-1979), Mary Tyler Moore (1970-1977), and M*A*S*H (1972-1983). There were some viewer complaints, but they were overshadowed by the positive responses from the public. In January of 1977, Roots was not only the most acclaimed and highest rated program of all time, it established the format for the miniseries. In the early 1980s, there was a renaissance in the genre of the TV drama, with shows that were even more authentic, like Hill Street Blues (1981-1987) and St. Elsewhere (1982-1988). By then, originally invented for rural areas where reception was bad and not in the majority of households yet, cable began offering programming that wasn’t available on network TV, such as uncut films, uninterrupted by commercials. By the end of the 1980s, 60% of households were wired for cable. The VCR also gained ground, with 68% of households owning one by the end of the decade. It also allowed viewers to rent or purchase movies.

From then on, “quality drama” grew from a specialized form to mainstream, and cable just grew. In 2018, 90.3 million households subscribed to cable/satellite TV, although statistics show that number has been dropping steadily, with viewers “cutting the cord,” and subscribing streaming services instead. Platforms like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon have wooed viewers away with original programming like House of Cards and The Incredible Mrs. Maisel. Creating their own content also did away with the battle for the rights to air a program. Personalized experience has created an atmosphere where viewers can watch what they want, when they want, the “Netflix affect” giving instant fame to shows and stars who go viral. According to a 2019 study by consumer research center Horowitz, 15% of television viewers streamed on at least a weekly basis in 2010. In 2019, that number more than quadrupled to 65% of viewers. OTT devices – like Apple, Roku, Amazon Fire, and Sling – helped viewers to access content from high-speed internet to view on other devices, and took off during the 2010 cord cutting revolution.

Then came the pandemic, and everything ground to a halt, except for reality programming and talk shows, which were reduced to the audience basically viewing Zoom meetings, as was the recent Democratic convention. American Idol held online auditions, and it’s given a whole new meaning to The Masked Singer. Broadcasters have depended on an inventory of shows already produced, but not aired, delayed season premieres, and put shows on hiatus with the remaining episodes to be aired once production resumes. At present, some series have hesitantly gone back into production, but style and substance are now limited. Mark Johnson, veteran producer of Better Call Saul, has said, “Like a lot of other people, we’re going to have to be very creative in where and how we shoot. A lot of places just won’t let you in.” Tight controls have been put in place, crowd scenes are now a no-no, love scenes are now a challenge unless the actors are involved in real life, insurance companies are hesitant to cover productions, and writers face the dilemma of whether to set shows in the past or bring the pandemic into the plot. Mark Heyman, co-creator of Black Swan, The Skeleton Twins, and CBS’s Strange Angel, told the Washington Post, “Do you really want your stars wearing masks because that’s what characters would do? Do you want to have people engaging with each other in groups no larger than six? Do you want to write stories where everyone is at a safe distance? Because a lot of those things won’t be very much fun to watch.” Yet, if these things aren’t incorporated, a story won’t feel authentic. Subject matter has also become reduced. As Heyman also said, “It’s not easy to make a show about high school when there is no high school.”

So what happens now that television has become pandemically challenged? Will we be relegated to watching shows set before the present day, or characters performing their parts separately from little boxes? Will the use of a green screen become the norm? This pandemic too, shall pass. TV has survived a war, McCarthyism, WE’s Sex Box, and ABC’s Caveman. While television programming might have been put on pause, in my opinion, it will once again rise from the viral ashes to come back fresher and better.